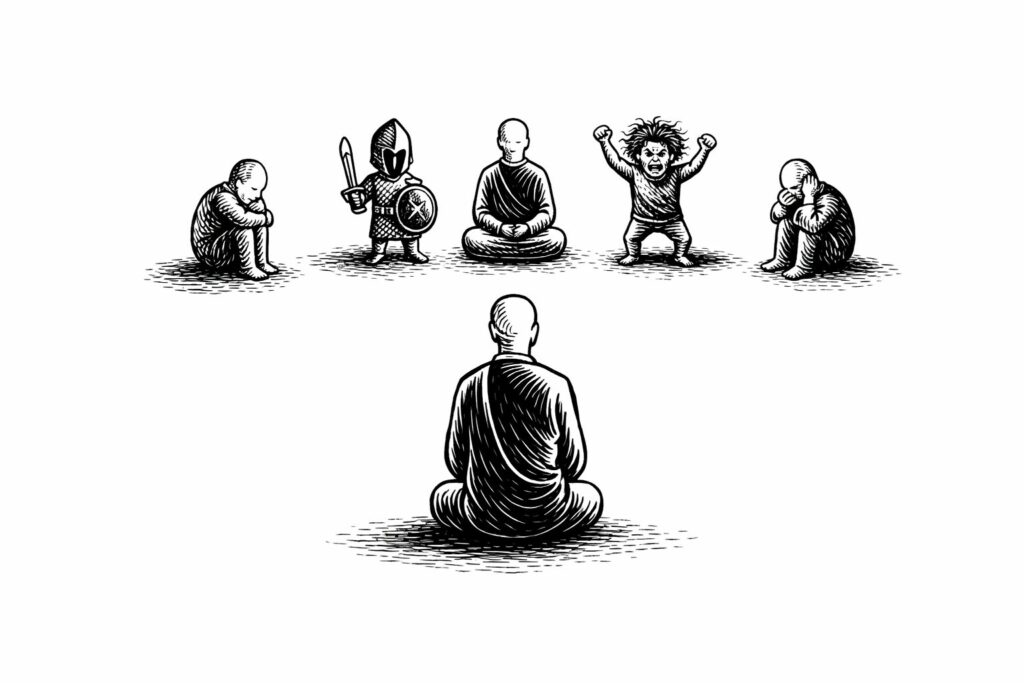

Human inner life is not singular.

Thoughts, impulses, emotions, and reactions often arise from different internal positions, each with its own priorities, fears, and strategies. Spiral Psychology understands this not as dysfunction, but as a natural consequence of development, learning, and adaptation.

This page introduces how Spiral Psychology works with inner parts—and how this approach differs from models that frame inner conflict as pathology.

Parts, Not Pathology

A central principle of Spiral Psychology is that inner parts are adaptive, even when their effects are painful or limiting.

What may appear as:

- self-sabotage

- avoidance

- emotional numbing

- inner criticism

- conflicting desires

is often the result of parts that learned to protect the system under specific conditions.

These parts are not mistakes.

They are strategies that once worked.

Difficulties arise when:

- old strategies remain active long after conditions have changed

- parts are forced into extreme or rigid roles

- one part dominates at the expense of the whole

Spiral Psychology approaches these patterns with curiosity and respect rather than suppression or control.

Influences and Lineage

Spiral Psychology draws from several established traditions that recognize inner multiplicity.

Most notably, it builds on Richard Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems (IFS) model, which demonstrated that:

- the psyche is composed of multiple parts

- parts have protective intentions

- healing occurs through relationship rather than eradication

In addition, Spiral Psychology resonates with insights from:

- ego state therapy

- trauma-informed psychology

- somatic and nervous-system–based approaches

- depth psychology

Rather than adopting any single model wholesale, Spiral Psychology integrates these perspectives into a coherent, safety-oriented framework aligned with the Spiral’s emphasis on return and embodiment.

What Is a “Part”?

In Spiral Psychology, a part refers to a pattern of perception, emotion, and behavior that:

- activates in specific contexts

- carries a particular role or function

- was shaped by lived experience

A part is not:

- a separate personality

- a defect

- an illusion

It is a functional configuration within a coherent person.

Some parts focus on:

- maintaining control or stability

- preventing emotional overwhelm

- seeking connection or meaning

- avoiding perceived danger

Parts often operate outside conscious awareness until they are recognized and met with attention.

Trauma, Parts, and Adaptation

Trauma plays a central role in how parts form and specialize.

When experience exceeds a person’s capacity to integrate it:

- certain aspects of experience are held outside ordinary awareness

- protective patterns emerge to preserve functioning

- parts take on roles that prioritize survival over flexibility

From this perspective:

- extreme reactions are often protective responses

- inner conflict reflects competing survival strategies

- resistance to change may signal unresolved safety concerns

Spiral Psychology does not attempt to override these patterns.

It works with them at the pace the system can tolerate.

The Ego and the Experience of a “Single Mind”

Most people experience themselves as having one mind—one center of decision, one sense of authorship, one “I” that feels in charge.

This experience is real and important.

In Spiral Psychology, the ego is understood as a localized field of coherence:

the organizing structure that supports continuity of identity, responsibility, decision-making, and participation in the world.

The ego is not an illusion to be dismantled.

It is the structure that allows integration to occur at all.

The “Mono-mind” Assumption

Traditional psychology often assumes what Richard Schwartz has called the dominant mono-mind model: the idea that a healthy psyche consists of a single, unified mind, and that internal conflict represents dysfunction.

Spiral Psychology departs gently from this assumption.

Rather than treating the sense of a single mind as the whole story, it treats it as:

- a coordinating experience

- produced by the ego’s organizing function

- which can coexist with inner multiplicity

From this perspective:

- the ego feels like “the one in charge” because it is the primary interface with action and accountability

- inner parts do not usually announce themselves as separate unless tension or overwhelm arises

This explains why multiplicity often goes unnoticed until stress, trauma, or change brings it into view.

Integration, Not Displacement

Importantly, Spiral Psychology does not replace the ego with another inner authority.

The work of parts integration happens through the ego’s coherence, not by bypassing it.

The ego:

- remains responsible for choice and action

- provides continuity across inner states

- serves as the primary channel through which parts can be recognized, communicated with, and integrated

Later sections of Spiral Psychology will introduce additional language for describing modes of presence and regulation that support this coordination. These are not presented as entities or hierarchies, but as capacities that operate within a coherent ego structure.

For now, it is enough to note this:

A coherent ego does not disappear when inner multiplicity is acknowledged.

It becomes a better listener.

Parts and the Spiral Cycle

Different Spiral phases tend to activate different parts.

For example:

- periods of disruption may mobilize protective or controlling parts

- descent phases may stir parts associated with memory or grief

- integration phases may require parts that support rest and consolidation

Understanding parts helps explain why Spiral movement is rarely smooth—and why resistance is often meaningful rather than obstructive.

A Note on Language and Care

Spiral Psychology uses the language of “parts” descriptively, not literally.

It does not assume:

- fragmentation

- disorder

- or loss of agency

Instead, it offers a way to:

- notice inner dynamics

- relate to them with respect

- and restore proportion where roles have become fixed

If at any point inner exploration feels destabilizing, the Spiral stance is to slow down, re-ground, and seek appropriate support.

Where This Leads

This understanding of inner parts lays the groundwork for:

- trauma-informed pacing

- archetypal pattern recognition

- deeper Spiral integration without inflation

Later sections explore how some parts resonate with symbolic patterns (archetypes)—and how to work with those patterns without losing psychological grounding.

Next: Working With Inner Parts